African Burial Ground in Elmhurst:

1828 – ?

The first church building of the United African Church and Cemetery, founded in 1828 on this site.

The Elmhurst History and Cemeteries Preservation Society, one of HDC’s 2018 Six to Celebrate groups, has submitted a Request for Evaluation to the Landmarks Preservation Commission to landmark the African Burial Ground in Elmhurst, Queens. This all volunteer group is working hard to raise awareness of the neighborhood’s cultural history–especially this site–which has been in limbo of impending development. It has miraculously remained untouched for nearly three centuries, but now it needs the help of greater community to ensure its survival.

The small plot of land at 47-11 90th Street has survived as a touchstone to one of the earliest freed African-American communities in the region. This parcel has a history that is nearly as old as freed African-American society in New York State itself. Founded one year after emancipation in 1828, newly freed African-Americans did not wait to form an identity or religion of their own, and swiftly established a congregation, the United African Society (later known as the African Methodist Episcopal Church), on the very site of the burial ground. Documentation has determined that there were 310 interments here, the majority of which remain beneath the earth today. This congregation evolved and splintered over the years; despite this, survived and lives on today as the St. Mark’s A.M.E. Church in North Corona.

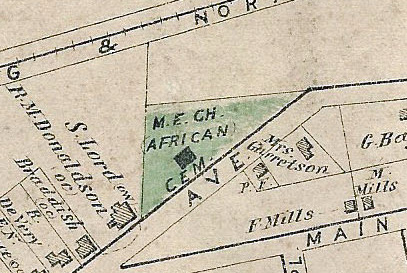

1859 detail of a map of Newtown, displaying the presence of the African Cemetery and a chapel building.

So inextricable are the burials of the Elmhurst site to St. Mark’s, that in 1928, the congregation attempted to move their deceased to its new location in North Corona. The City of New York declined to allow the congregation to move their dead, and only twenty remains were successfully transferred to the church’s new location at that time. It is both remarkable that the African-American direct descendant congregation is still active, and that the plot of land where their roots began–and which still contains never-disturbed burials—persists, barely touched, in an ever-changing city.

Nearly forgotten, vast public interest of this site was awakened after Martha Peterson was found in her iron coffin in 2011. Ms. Peterson’s life—and death—is now the subject of a special program, which debuted on P.B.S. last month.

2018 satellite image of African Burial Ground, which has never been developed.

While there are no physical markers that remain of this little cemetery, in 2012, the LPC designated the Brinckerhoff Cemetery for its role in the early Dutch settlement in Queens. Like the African cemetery, there is no physical evidence at Brinckerhoff that indicates it as a graveyard any longer. Despite the lack of gravestones, the LPC found Brinckerhoff Cemetery to contain sufficient historical and archaeological significance to merit landmarking. The LPC Vice Chair at the time remarked that Brinckerhoff was “a place of remembrance” and “sacred in many ways.” HDC believes that these ideals apply just as much to the Elmhurst graveyard.

The Elmhurst site is incredibly culturally significant to our shared history, and, like most places of African-American history, is long neglected and cast aside. Designating this tiny surviving fragment would vow an act of parity and an official acknowledgement of the early, freed African-Americans in 19th Century Queens. With so few landmarks and no designated historic districts in Elmhurst, tell the LPC, Queens Councilmember Dromm, and Queens Borough President Melinda Katz that the time to act is now!