- Harriet and Thomas Truesdell House – 227 Duffield Street

- 2020 Grassroots Award Presentation – Dorrance Brooks Property Owners and Residents Association and St. Marks Independent Block Association

- Addisleigh Park

- Tin Pan Alley

- Lewis H. Latimer House

- African Burial Ground

- Weeksville

- Statement on George Floyd and Systemic Racism

Harriet and Thomas Truesdell House – 227 Duffield Street

The Historic Districts Council has long been concerned about the permanent preservation of the Harriet and Thomas Truesdell House at 227 Duffield Street in Downtown Brooklyn. The house, dating from the mid-19th century, was home to the Truesdells from 1851 – 1863, and is the home where Harriet died in 1862. The Truesdells were intimately involved in the American Abolitionist movement, befriending such luminaries as Ralph Waldo Emerson and William Lloyd Garrison. The Truesdells were associated with the house until the 1920s.

The history of slavery in Brooklyn and New York City is a field which is still very much emerging. More research needs to be done and much more information needs to be incorporated into the accepted canon of history. As preservationists and historians, we should be doing everything possible to save and record the stories, records and artifacts of that time before they are lost. As much of early American life took place in the domestic realm, especially the organizing and formulation of controversial reform movements such as Abolitionism, the designation of a site of conscience such as 227 Duffield Street as an individual New York City landmark would grant protection to a building which will only grow in importance and significance as our understanding of history expands. 227 Duffield Street was designated as an Individual Landmark on February 2, 2021.

2020 Grassroots Award Presentation – Dorrance Brooks Property Owners and Residents Association and St. Marks Independent Block Association

Grassroots Award winners Dorrance Brooks Property Owners and Residents Association and St. Marks Independent Block Association discuss the preservation concerns in their neighborhoods. During the presentation Keith Taylor gives the history of Dorrance Brooks Square, named after Dorrance Brooks, an African American soldier who died in France shortly before the end of World War I. A native of Harlem and the son of a Civil War veteran, Brooks was a Private First Class in the 15th Infantry/369th Infantry Regiment. The Dorrance Brooks Square Historic District was Calendared on February 2, 2021.

Addisleigh Park

179-07 Murdock Avenue, former home of singer Ella Fitzgerald and jazz musician Ray Brown

Built when race-restricted covenants dictated the segregation of the city’s neighborhoods, Addisleigh Park eventually transformed from an exclusively white neighborhood into one of New York City’s premier African American enclaves by the early 1950s. The area would eventually become home to notables such as Count Basie, Lena Horne, Ella Fitzgerald, Illinois Jacquet, Jackie Robinson, James Brown, Joe Louis, Milt Hinton, Roy Campanella, Percy Sutton, Cootie Williams and many others.

HDC Addisleigh Park Neighborhood Survey

Tin Pan Alley

“Tin Pan Alley had an indelible impact on the history of American popular music and paved the way for what would become “the Great American Songbook.” However, arising during the period following the Civil War and the failure of Reconstruction, when Jim Crow laws and other unjust, discriminatory practices were reversing newly won freedoms and rights for African Americans and entrenching systemic racism throughout American society, racist caricatures and stereotypes of African Americans were increasingly spread through mass media, including sheet music produced on Tin Pan Alley. At the same time, Tin Pan Alley’s music publishing brought ragtime to an international public, offered unprecedented opportunities for African American artists and publishers to create mainstream American music, and saw many gain acclaim and prominence. The proposed designation of this row of five buildings, which represent the history of Tin Pan Alley, recognizes the significant contributions and achievements of African Americans here, and acknowledges the harsh realities they faced.” Tin Pan Alley Designation Report

Six to Celebrate Cultural Landmarks – Lewis H. Latimer House, Queens

Latimer House was the home of African American inventor and electrical pioneer Lewis Howard Latimer from 1903 until his death in 1928.

Six to Celebrate Cultural Landmarks – African Burial Ground

1-African Burial Ground Monument

The African Burial Ground is considered the largest colonial- era cemetery for enslaved African people, and in addition to being of great historical and spiritual significance, is a major resource for the study of the African diaspora. The African Burial Ground is part of the African Burial Ground & The Commons Historic District; a National Historic Landmark and listed on the State and National Register of Historic Places.

Weeksville / Houses on Hunterfly Road

Four wooden houses remain along the old Hunterfly Road, within the boundaries of what was once Weeksville, a nineteenth-century free black community that is now known as Bedford-Stuyvesant. The road, documented as early as 1622, was an avenue of communication under British rule; it fell into disuse with the installation of the grid system in 1838. Each building was designated as an Individual Landmark on August 18, 1970. The Weeksville Heritage Center is a historic site and cultural center that uses education, arts and a social justice lens to preserve, document and inspire engagement with the history of Weeksville.

Statement on George Floyd and Systemic Racism

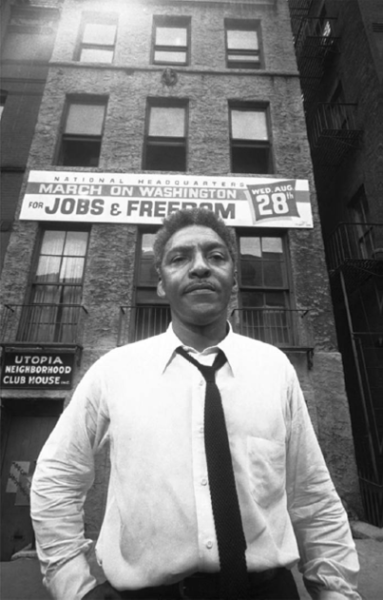

Bayard Rustin in front of the National Headquarters for the March on Washington for Jobs & Freedom Associated Press, “March on Washington,” photographer: anonymous, August 1963

From “Central Harlem – West 130th-132nd Streets Historic District” Designation Report, NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission, 2018

Everything the Historic Districts Council does starts and ends in community. Although our work is based on place, places mean nothing without people and it is the vibrant, safe, sharing, equal treatment of people which animates our work and drives our mission. Implicit in HDC’s work to advocate for historic places is the belief that places are for everyone. We titled our annual conference “Open to the Public” for this reason.

HDC is horrified by the killing of George Floyd, who was slain not only because of the actions of a few police officers but also because of centuries of implicit barriers erected to divide and demonize communities. The tragedy of Mr. Floyd’s death is multiplied over and over by the countless African Americans, people of color and other minorities who have been stolen from, imprisoned, abused, beaten and murdered by a societal system which allows blatant discrimination to continue to exist, if not flourish. Breonna Taylor was killed by police, Ahmaud Arbery was gunned down while jogging, bird watcher Christian Cooper was falsely accused and threatened with institutional violence because he spoke up about a dog being illegally off-leash, NYC teacher Rana Mungin died after being twice denied a COVID-19 test and these are only the well-known victims of systemic racism from the past few months. The list goes on endlessly and no one who believes in a just and equitable society can let this stand or continue.

It would be simple for HDC to “stay in our lane” and keep silent about this issue which doesn’t appear to affect historic buildings (save those which have been harmed) but we believe that would both be wrong and incorrect. It would be wrong because remaining silent about a grave injustice is to condone it and we all have done that for too long. It would be incorrect because the goal of preserving historic buildings is to build a better future and without changing our society, that would be impossible.

We owe to our successors to do everything we can to build a better future; we owe it to ourselves to make a better present.

Here are some links to help forward this conversation:

- Anti-racism Resources: https://www.goodgoodgood.co/

anti-racism-resources - Jane Elliot is a renowned teacher of anti-racism. Here is a recent interview with her talking about current events: https://youtu.be/_26bpU7UgTs; and here she is speaking on the Oprah Winfrey show in 1992 about anti-racismeducation: https://youtu.be/0HsXAIzYklk.

- 75 Things White People Can Do for Racial Justice: https://medium.com/equality-

includes-you/what-white- people-can-do-for-racial- justice-f2d18b0e0234 - 10 Organizations Supporting the Black Lives Matter movement in NYC: https://www.6sqft.com/10-

organizations-supporting-the- black-lives-matter-movement- in-nyc/ - National Police Accountability Project

- Black Visions Collective

- Campaign zero