- Ada Louise Huxtable

- Ella Fitzgerald

- Lady Deborah Moody

- Walentyna Janta-Połczyński (née Stocker)

- Audre Lorde

- Emma Goldman

- Odetta

- Margaret Sanger

- Alice Austen

- Jane Jacobs

- Margaret Cochran Corbin

- Billie Jean King

- Edith Wharton

Ada Louise Huxtable

Ada Louise Huxtable (1921-2013), a native New Yorker, was a pioneer in architectural criticism, and a champion of livable cities. As the first full-time architecture critic at a major American newspaper (The New York Times created the position specifically for her in 1963), she won the first Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism in 1970, and helped redefine architecture in the public consciousness as “a very real and important art [because] it affects us all so directly.” Her writing on architecture, urban design, and planning helped bring those topics into the popular consciousness, and encouraged New Yorkers to see the buildings around them as part of their lives. She championed “humanity of scale,” and buildings that were “integrated into life and use,” writing: “what counts more than style is whether architecture improves our experience of the built world; whether it makes us wonder why we never noticed places in quite this way before.” Huxtable helped us do exactly that. On this virtual tour of her New York, we will learn about her life, see buildings she praised and those she decried, and consider her legacy as a writer, an urbanist, and a champion of the collective work of city-making.

Watch a virtual walking tour Ada Louise Huxtable’s New York.

Ella Fitzgerald

Ella Fitzgerald (1917-1996), famed jazz singer noted for her purity of tone, impeccable diction, phrasing, timing, intonation, and a “horn-like” improvisational ability, particularly in her scat singing called Queens home from 1949 to 1956. Her musical collaborations with Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and The Ink Spots were some of her most notable acts outside of her solo career. These partnerships produced some of her best known songs such as “Dream a Little Dream of Me”, “Cheek to Cheek”, “Into Each Life Some Rain Must Fall”, and “It Don’t Mean a Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing)”. Fitzgerald was a civil rights activist; using her talent to break racial barriers across the nation. She was awarded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Equal Justice Award and the American Black Achievement Award. In 1949, Norman Granz recruited Fitzgerald for the Jazz at the Philharmonic tour. This tour specifically targeted segregated venues and Granz required promoters to ensure that there was no “colored” or “white” seating. He ensured Fitzgerald received equal pay and accommodations regardless of her sex and race and if these conditions were not met, shows were canceled. She was recognized as a “cultural ambassador,” receiving the National Medal of Arts in 1987 and America’s highest non-military honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

She and her husband lived at 179-07 Murdock Avenue, Queens in the Addisleigh Park Historic District. Built when race-restricted covenants dictated the segregation of the city’s neighborhoods, Addisleigh Park eventually transformed from an exclusively white neighborhood into one of New York City’s premier African-American enclaves by the early 1950s. Lured by the promise of seclusion, quietude, space and beauty, many of the newcomers were world-famous. The area would eventually become home to notables such as Count Basie, Lena Horne, Illinois Jacquet, Jackie Robinson, James Brown, Joe Louis, Milt Hinton, Roy Campanella, Percy Sutton, Cootie Williams and many others.

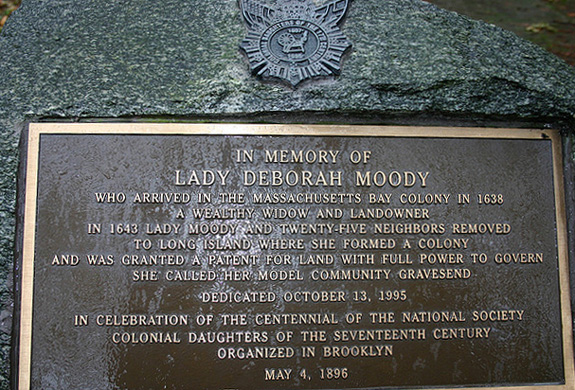

Lady Deborah Moody

Lady Deborah Moody (1586– circa 1659), was an English expatriate who helped develop Gravesend, Brooklyn. Born in London, Moody left England in 1639 due to religious persecution, as she had adopted Anabaptist beliefs. She settled in Saugus, Massachusetts where she was put on trial and eventually excommunicated for allegedly spreading religious dissent. Puritan leader John Endecott described her as a “dangerous woman” during her trial. Moody and her fellow Anabaptists found a new home in the Dutch colony of New Netherland since the Netherlands and their colonies had policies of relative religious tolerance. The Dutch West India Company entrusted Moody with the southwestern tip of Long Island. This includes the areas of south Brooklyn encompassing parts of what is now known as Bensonhurst, Coney Island, Brighton Beach, and Sheepshead Bay. Moody named her new community Gravesend and allowed total religious freedom in Gravesend, as long as it fell within the laws of the colony. Gravesend was the first New World settlement founded by a woman. Lady Moody’s settlement is marked by the designated Old Gravesend Cemetery which holds remains of early settlers (although none contemporary with Lady Moody) and the designated 18th century Van Sicklen House, which occupies the site where her home may have stood.

Walentyna Janta-Połczyński (née Stocker)

During World War II, Walentyna Stocker (1913-2020) was the primary secretary and translator for the Prime Minister of the Polish Government-in-Exile. Walentyna (pronounced “Valentina” in English) translated reports from the Polish Underground State into English which first revealed Nazi atrocities–including the existence of concentration camps in German-occupied Poland–to the United Nations. Walentyna’s translations revealed the humanitarian crisis occurring in Europe to the Allies, putting her at the center of Polish intelligence during the War.

Walentyna also kept the Polish resistance alive from abroad, organizing and broadcasting Dawn, a secret radio station to Poland. Her service didn’t end after the War – she joined the Women’s Auxiliary Service in the rank of Second Lieutenant in the Polish Army. In this role, she worked with concentration camp survivors and prisoners-of-war, and was present at the Nuremberg Trials. She was recognized in 2011 with the Medal of Merit for Polish Culture by Poland’s Ministry of Culture and National Heritage and received the Jan Karski Eagle Award in 2016. Her life will be honored with a state funeral in Poland in 2021. A coalition of local activists seeks to honor her life by securing landmark status of her chosen and adopted home of Elmhurst, Queens.

Walentyna’s husband Aleksander was a Polish author and reporter. He was living in Paris when Germany invaded Poland, and promptly joined the Polish Army there. When the Nazis captured France, Aleksander concealed his Polish identity and played the role of a Frenchman, as it was known among soldiers that Nazi treatment of Polish partisans was especially brutal. He passed as a French prisoner-of-war and was kept as a slave by a German family until his escape to England in 1942.

While Walentyna and Aleksander were in France and later England during the same time, they didn’t meet until they each moved to Buffalo, New York after the War. They married only five months after meeting, and left Buffalo for New York City in 1955. They made their home in Elmhurst (88-28 43rd Avenue) by 1960, and their house was known as the nucleus of the Polish émigré elite in the United States. Walentyna remained here until her death at 107 years old in April 2020.

The Landmarks Preservation Commission did not landmark the house despite community requests. It was demolished in 2022.

Audre Lorde

From 1972 to 1987, acclaimed African-American lesbian, writer and activist Audre Lorde (1934-1992) lived at 207 St. Paul’s Avenue, Staten Island with her two children, Elizabeth and Jonathan, and her partner, Frances Clayton. Her house is a NYC Individual Landmark and located in the St. Paul’s Avenue-Stapleton Heights Historic District. Lorde accomplished a great deal while living there, including the publication of numerous influential books, poems, articles and essays that dealt with the issues of civil rights, feminism and lesbianism; held positions as professor of English at John Jay College and as the Thomas Hunter Chair of Literature at Hunter College; spoke at the 1979 National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights; co-founded Kitchen-Table: Women of Color Press and was bestowed with many honors, including the Borough of Manhattan President’s Award for Literary Excellence in 1987. From 1991 until her death from liver cancer the following year, Lorde was the New York State Poet Laureate.

Emma Goldman

From 1903 to 1913, the tenement at 208 East 13th Street, Manhattan was the home of the anarchist and revolutionary Emma Goldman (1869-1940), a Jewish immigrant from Lithuania (then part of the Russian Empire). Goldman wrote and lectured in support of women’s rights, birth control, free speech, sexual freedom and labor unions. Beginning in 1906, she published a monthly periodical , in which she and other radical thinkers and artists expressed their ideas entitled “Mother Earth” from the tenement building next door at 210 East 13th Street. Her lectures, given all over the country, drew large crowds, and her activism led to multiple arrests, the last of which would be for her anti-draft activism at the beginning of the United States’ involvement in World War I. She and her long-time partner and fellow-anarchist, Alexander Berkman, were imprisoned for two years. After her release from prison in 1919, the federal government, under the Anarchist Exclusion Act, deported Goldman and 248 others, including Berkman, back to Russia. She continued to write and support human rights and political causes, spending time in England, Canada, France and Spain before she died in 1940 in Toronto, Canada.

Odetta

*Odetta (1930- 2008), born Odetta Holmes, was an influential artist/activist of the civil rights generation. During her 60-year career, she influenced numerous performers, including Harry Belafonte, Bob Dylan, Joan Baez and Janis Joplin. Her signature song was “This Little Light of Mine.” Odetta took part in the historic freedom marches of the 1960s in Selma, Alabama, and in Washington, D.C. Martin Luther King, Jr. named her “Queen of American Folk Music.” President William J. Clinton honored her with the National Medal of Arts, saying, “Odetta reminds us all that songs have the power to change the heart and change the world.”

*Text from the Cultural Medallion placed on 1270 Fifth Avenue, Manhattan

Margaret Sanger

From 1930 to 1973, the Greek Revival style townhouse at 17 West 16th Street, Manhattan was home to the clinic of birth control pioneer Margaret Sanger (1879-1966). Sanger moved to New York City in 1911 and began working as a nurse on the Lower East Side, where she treated women with frequent births, miscarriages and self-induced abortions. At the time, birth control, a term she popularized, was not available in the United States, and the 1873 federal Comstock law prohibited the distribution of information on the topic. Despite this, in 1914, Sanger founded a monthly newsletter entitled The Woman Rebel and was subsequently indicted for sending “obscene” material through the mail. In 1916, Sanger opened her first clinic in Brownsville, Brooklyn, and in 1921 she helped found the American Birth Control League, which later became known as the Planned Parenthood Federation of America. In 1930, she established a more permanent home for her Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau at 17 West 16th Street, where research was performed, patients were treated and instructed on contraceptives, and medical professionals from across the country were educated about sex, contraception and disease until 1973. The Greek Revival style townhouse, today a private residence, still stands as a reminder of Margaret Sanger’s groundbreaking work to advance women’s health and quality of life, is a NYC Individual Landmark and a National Historic Landmark.

Alice Austen

Alice Austen (1866 – 1952) was a pioneer of American photography who lived and worked at 2 Hylan Boulevard, Staten Island with her partner Gertrude Tate. Austen took over 7,000 photographs of a rapidly changing New York City, making significant contributions to photographic history, showing New York’s immigrant populations, Victorian women’s social activities, and the natural and architectural world of her travels. What is especially significant about Austen’s photographs is that they provide rare documentation of intimate relationships between Victorian women. Her depiction of her non-traditional lifestyle and that of her friends, although intended for private viewing, is the subject of some of her most critically acclaimed photographs. Her former home is now the site of the Alice Austen House Museum and a nationally designated site of LGBTQ history.

Jane Jacobs

From 1947 to 1968, 555 Hudson Street, Manhattan was the home of author, urban theorist and activist Jane Jacobs (1916-2006). While it is not certain whether she wrote her 1961 seminal work “The Death and Life of Great American Cities” here, she did often reference her home in Greenwich Village while extolling the virtues of thriving urban settings with bustling sidewalks and small-scale, mixed-use buildings —like 555 Hudson. She wrote and spoke out against the then-rising practice of slum clearance and urban renewal, and was instrumental in the fight to save the South Village, SoHo and Little Italy from Robert Moses’ Lower Manhattan Expressway. Her work heavily influenced contemporary urban thought, despite urban planners who, at the time, criticized her lack of formal education. Today, her legacy is celebrated every May with Jane’s Walks — volunteer-led walking tours in urban neighborhoods throughout the world. Jane Jacobs’ former residence is located in the Greenwich Village Historic District.

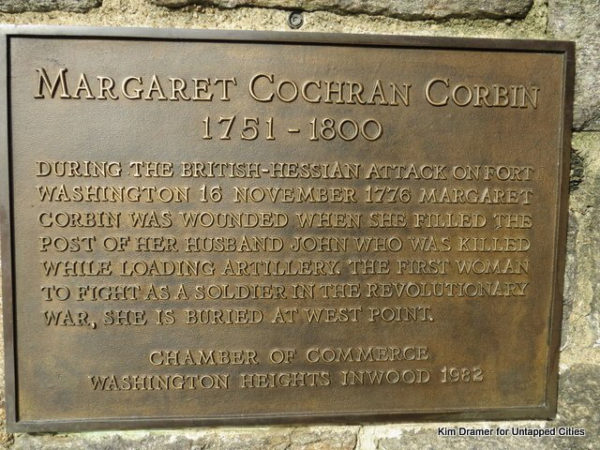

Margaret Cochran Corbin

Margaret Cochran Corbin (1751-1800) was the first American woman to receive a military pension for her service during the Revolutionary War. When her husband, John Corbin, enlisted in the army to fight for the colonists, Margaret decided to go with him as a “camp follower” to cook, do laundry and nurse the wounded. On November 16, 1776, Corbin assisted her husband in operating a cannon during a Hessian attack on Fort Washington (today’s Fort Tryon). When John was fatally wounded, Margaret heroically took over his post and continued to fire at the enemy. Before the four-hour battle was through, she was severely wounded and nearly lost her left arm. In 1779, the Continental Congress awarded her a lifelong pension equivalent to half that of a male veteran. She died at age 49 and was buried in Highland Falls, NY, but in 1926, the Daughters of the American Revolution had her remains moved to the cemetery at the U. S. Military Academy at West Point, where she is the only Revolutionary War soldier buried on the academy grounds. Today, a plaque in Fort Tryon Park honors her bravery and both the park drive and circle are named for her.

Billie Jean King

In 2006, the USTA National Tennis Center in Flushing Meadow Corona Park, Queens was rededicated as the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center, in honor of King’s remarkable tennis career and her activism for women’s and LGBTQ rights. Between 1961 and 1979, King (born 1943) won 39 Grand Slam titles, including a record 20 Wimbledon titles. Both during the height of her career and after, King fought for equal prize money for women, who were paid considerably less than their male counterparts. In 1973, she formed the Women’s Tennis Association and was its first president. As a result of her advocacy, the U.S. Open became the first major tournament to offer equal prize money. In 1981, King was publicly outed as a lesbian in a palimony suit and lost all of her endorsement deals, yet she continued to fight against discrimination. She was elected to the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1987 and awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009 by President Barack H. Obama for her advocacy work. The USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center is a major attraction in the last weeks of summer, when international crowds flock to Queens for the U.S. Open, one of the most prestigious tennis tournaments in the world.

Edith Wharton

Edith Jones Wharton (1862-1937), one of America’s most important authors, lived at 14 West 23rd Street, Manhattan at a time when 23rd Street marked the northern boundary of fashionable New York. There, in her father’s extensive library, young Edith Jones discovered the world of literature. Wharton wrote with authority on gardens and design, but was most celebrated for her fiction. Her novels and stories are characterized by her intelligence, perception and the great beauty of her prose. Wharton lived in France for the latter part of her life, but the complex world of patrician New York remained the source of her greatest fiction. This includes The House of Mirth (1905) and The Age of Innocence (1920), for which, in 1921 she became the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Literature.