HDC’s Spanish Language Fellow, Diego Robayo, documents life throughout the city’s boroughs with photographs and interviews of significant Latino cultural heritage. Research on Casa Latina and other Latino landmarks across the city was made possible by the support of the New York Community Trust. This article was also published in the Manhattan Times and in This is The Bronx Info.

Born in a small town in Galicia, in northern Spain, Vicente Barreiro came to New York in 1960 at the age of 15 with his mother and siblings. He has lived in East Harlem most of his life, and has played an important role in the history of the city’s Latino community.

But first it was Barreiro’s grandfather who came to the United States in the 1920’s, a time when the first immigration restrictions started to be enacted. In 1917, the Literacy Act became the nation’s first widely restrictive immigration law, implementing literacy tests for immigrants over 16 years old. Newly arrived immigrants had to demonstrate reading comprehension in any language. This law also established a higher tax for them upon their arrival.

Also, the Immigration Act, known as the Johnson-Reed Act, was enacted in 1924, and it limited immigration to two percent of any given nation’s residents already in the U.S. as of 1890. It made it difficult for Barreiro’s mother to join her husband, and she had to wait 20 years before she was able to come to America with her sons.

When they finally arrived, the green steppes of Vicente’s small town in Spain were replaced by the dark streets of the Lower East Side.

The young teenaged Barreiro did not understand at first why his family was leaving Galicia.

At that time, he could not accept that his family was leaving Spain, but today, more than 60 years later, Barreiro believes that having come to New York was the best decision his mother could have ever made.

As a student, Barreiro attended a school that espoused a community-centered approach to learning and the importance of integration and bilingual education, so most of his classes were taught in Spanish.

After graduating from high school, he worked at a textile factory, and then at a factory that manufactured bullets for the Vietnam War. He described those experiences as miserable, because he was not yet fluent in English and his employers cared little about employee welfare.

Barreiro recalls how his nineteen-year-old self saw the city streets as gray, and the people cold and indifferent.

As he describes it, his entire life seemed worthless, until someone brought color to it.

Her name was Cristina, and she was the woman that Vicente would eventually marry and spend the rest of his life with.

Cristina’s father, Alfonso Rubio, had immigrated to New York from Argentina in the 1920’s. After a decade of living in the States, Rubio had saved enough money to purchase a pickup truck from which he would sell cassettes and vinyl records to East Harlem’s Puerto Rican population.

As the Puerto Rican population in East Harlem grew, so did Rubio’s business. Puerto Ricans retained a strong affinity for their rhythms, and Rubio drove his truck around East Harlem to satisfy their demand for music. In the 1960’s, he had done so well financially that he was able to purchase his own store at Lexington Avenue and East 116th Street.

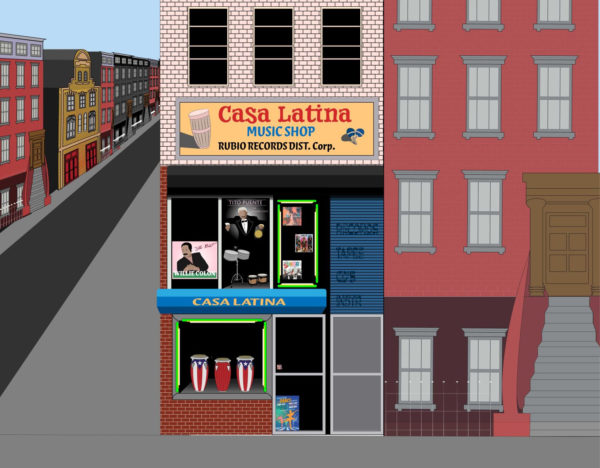

At the age of 21, after marrying Cristina, Barreiro left the dark factories behind and began to work in his father-in-law’s music store. The family business thrived, and in 1969, they were able to buy Casa Latina, a Latin music store located just a few houses away that had been established in 1948.

The new Casa Latina soon positioned itself as a store where people would be able to find any artists related to Puerto Rican music and folklore. The store was constantly jammed with customers attracted by its extensive and impressive collection.

“Celebrating is part of Puerto Rican culture,” explains Barreiro. “And they are very loyal customers.”

To meet the demand, Barreiro and his family stacked a wide selection of vinyl records and cassettes that included each the most popular and emerging salsa artists from Latin America. They installed glass cabinets through the entire store and stocked them with music, instruments, books and clothes – all of them related to Latin culture.

Barreiro himself soon became an expert in salsa music and all its forms.

Cristina says customers would only need sing a small part of a song or mumble its rhythm, and Barreiro would immediately know what song and artist they were referring to.

Casa Latina soon became an iconic house of music, and it began to attract renowned artists, such as Tito Puente and Marc Anthony, who sought out their fans in addition to tourists visiting New York City from as far away as Japan.

As the Barreiro family remembers it, large crowds would gather to revel in the music and dance.

The 1970’s and 1980’s were Casa Latina’s golden years.

The population in East Harlem was then predominantly Puerto Rican and local residents were accustomed to hitting Casa Latina for the latest release or pick up an old favorite.

As the Puerto Rican population decreased, newer residents hailed from Mexico and the Dominican Republic, among other countries. Barreiro adjusted the store’s selections to tap into the new market and demographics. The store soon boasted shelves of the recordings of Mexican and other artists. Though sales are not what they once were, the family is committed to the neighborhood and to its residents.

Change is the natural course of neighborhoods.

The buildings and public spaces around us are there to remind us of all the people who came before us, and their preservation is an integral way to acknowledge and respect that unique history.

Buildings may change their use, but their characteristics and stories are monuments to preceding communities.

Places like Casa Latina and their contributions to specific cultures was so transcendent that their absence would erode history.

Una Casa con Herencia

Nacido en un pequeño pueblo de Galicia, en el norte de España, Vicente Barreiro llegó a Nueva York en 1960 a la edad de 15 años con su madre y sus hermanos. Ha vivido en East Harlem la mayor parte de su vida y ha jugado un papel importante en la historia de la comunidad latina de la ciudad.

Pero primero fue el abuelo de Barreiro quien vino a los Estados Unidos en la década de 1920, un momento en que comenzaron a promulgarse las primeras restricciones a la inmigración. En 1917, la Ley de Alfabetización se convirtió en la primera ley de inmigración ampliamente restrictiva del país, implementando pruebas de alfabetización para inmigrantes mayores de 16 años. Los inmigrantes recién llegados tenían que demostrar comprensión de lectura en cualquier idioma. Esta ley también estableció un impuesto más alto para ellos a su llegada.

Además, la Ley de Inmigración, conocida como la Ley Johnson-Reed, fue promulgada en 1924 y limitaba la inmigración al dos por ciento de los residentes de cualquier nación que ya se encontraban en los Estados Unidos a partir de 1890. Esto dificultó que la madre de Barreiro se uniera a su esposo, y tuvo que esperar 20 años antes de poder venir a Estados Unidos con sus hijos.

Cuando finalmente llegaron, las verdes estepas de la pequeña ciudad de Vicente en España fueron reemplazadas por las oscuras calles del Lower East Side.

El joven adolescente Barreiro no entendió al principio por qué su familia se estaba yendo de Galicia.

En ese momento no podía aceptar que su familia se fuera de España, pero hoy, más de 60 años después, Barreiro cree que haber venido a Nueva York fue la mejor decisión que su madre pudo haber tomado.

Como estudiante, Barreiro asistió a una escuela que propugnaba un enfoque de aprendizaje centrado en la comunidad y la importancia de la integración y la educación bilingüe, por lo que la mayoría de sus clases se impartían en español.

Después de graduarse de la preparatoria, trabajó en una fábrica textil, y luego en una fábrica que producía balas para la Guerra de Vietnam. Describió esas experiencias como miserables, porque todavía no dominaba el inglés y a sus empleadores les importaba poco el bienestar de los empleados.

Barreiro recuerda cómo su yo de diecinueve años veía las calles de la ciudad grises, y a la gente fría e indiferente.

Como él lo describe, toda su vida parecía inútil, hasta que alguien le dio color.

Su nombre era Cristina, y era la mujer con la que Vicente finalmente se casaría y pasaría el resto de su vida.

El padre de Cristina, Alfonso Rubio, había inmigrado a Nueva York desde Argentina en la década de 1920. Después de una década de vivir en los Estados Unidos, Rubio había ahorrado suficiente dinero para comprar una camioneta desde la cual vendía casetes y discos de vinilo a la población puertorriqueña de East Harlem.

A medida que creció la población puertorriqueña en East Harlem, también creció el negocio de Rubio. Los puertorriqueños conservaron una gran afinidad por sus ritmos, y Rubio condujo su camioneta por East Harlem para satisfacer su demanda de música. En la década de 1960, le fue tan bien económicamente que pudo comprar su propia tienda en la avenida Lexington y la calle 116 este.

A los 21 años, después de casarse con Cristina, Barreiro dejó atrás las fábricas oscuras y comenzó a trabajar en la tienda de música de su suegro. El negocio familiar prosperó, y en 1969, pudieron comprar Casa Latina, una tienda de música latina ubicada a pocas casas de distancia de la que montaron en 1948.

La nueva Casa Latina pronto se posicionó como una tienda donde la gente podía encontrar artistas relacionados con la música y el folclore puertorriqueños. La tienda estaba constantemente atestada de clientes atraídos por su extensa e impresionante colección.

“Celebrar es parte de la cultura puertorriqueña”, explica Barreiro. “Y son clientes muy leales”.

Para satisfacer la demanda, Barreiro y su familia acumularon una amplia selección de discos de vinilo y casetes que incluían a cada uno de los artistas de salsa más populares y emergentes de América Latina. Instalaron gabinetes de vidrio en toda la tienda y los abastecieron de música, instrumentos, libros y ropa, todos ellos relacionados con la cultura latina.

El propio Barreiro pronto se convirtió en un experto de la música salsa y todas sus formas.

Cristina dice que los clientes solo necesitaban cantar una pequeña parte de una canción o tararear su ritmo, y Barreiro sabría inmediatamente a qué canción y artista se referían.

Casa Latina pronto se convirtió en una casa emblemática de la música, y comenzó a atraer artistas de renombre, como Tito Puente y Marc Anthony, quienes salían a la búsqueda de sus admiradores además de turistas que visitaban la ciudad de Nueva York desde lugares tan lejanos como Japón.

Como lo recuerda la familia Barreiro, grandes multitudes se reunían para deleitarse con la música y el baile.