The NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission has scheduled four “special hearings” this fall to consider 95 proposed landmarks that have been on the agency’s calendar for five years or more. Back in November 2014, the LPC attempted to “de-calendar” all of these items, but since agreed to let the public weigh in. Below is HDC’s testimony for the third hearing on November 5, which is the first of two hearings for all items in Manhattan. The second hearing will be on November 12.

Item I-C

EXCELSIOR POWER COMPANY BUILDING, 33-43 Gold Street, Manhattan

LP –2359

Landmark Manhattan Block: 77 Lot: 24 (in part)

The Excelsior Power Company Building was designed by William Milne Grinnell and completed in 1888. Grinnell was trained as an architect at Yale University, but never practiced architecture professionally. This creation in brick and terra cotta, however, is proof of his architectural expertise. The seven-story building is a monumental Romanesque Revival industrial building, complete with rough-cut ashlar and rounded, springing arches. Queen Anne terra cotta details adorn the building, while the Art Nouveau letters that read “Excelsior Power Co. Bldg 1888 A.D.” add the final touch.

This is the oldest power generating station in New York City. Eleven power plants, whose energy helped grow New York into the city that it is, have been demolished throughout the five boroughs. The Excelsior Power Company Building, which is an architectural anomaly in the Financial District, has been successfully adaptively reused as residences despite its original industrial use. This building remains intact and has overcome functional obsolescence, and is a gift to Gold Street.

Item 1-D

57 SULLIVAN STREET, Manhattan

LP – 2344

Landmark Site: Manhattan Block 489, Lot 2

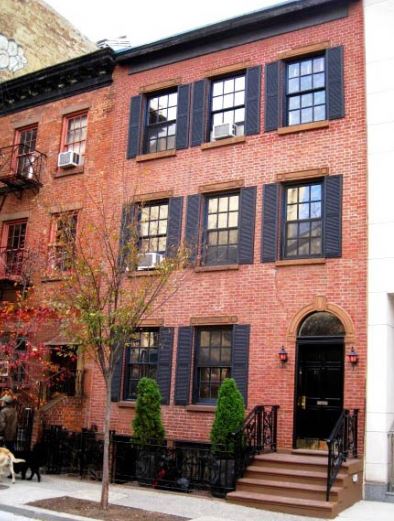

57 Sullivan Street was built in 1816-17, making it one of the oldest buildings in Manhattan. Standing just north of Broome Street, it is a three-bay, wood-framed rowhouse which, in the words of the Landmarks Preservation Commission’s statement of significance, “was designed in the Federal style, characterized by a brick-clad front façade laid in Flemish bond, incised paneled brownstone lintels, an incised entry arch with a keystone and impost blocks, and a stoop.” The fact that it is wood-framed makes it a rare example of the Federal period.

Originally two stories, by 1858 the building was raised to three, terminating in a wooden cornice. Its present owners acquired the house in 1995, and embarked on a restoration, including a new front door, windows, ironwork and shutters. It is possible that they were influenced in their choices by 203 Prince Street, an 1834 Federal house a couple of blocks away, designated an individual landmark in 1974.

57 Sullivan was calendared for designation in 1970. It was also one of 13 Federal houses proposed for designation in 2002 by preservation organizations, but was not heard until 2009. It enjoyed strong support from local officials, neighbors and preservation groups. Any alterations that might have prevented its designation at that time were certainly consistent with those on other extant buildings of the time, as 203 Prince Street shows. While the building’s owners have been careful stewards of the property, development pressure and a great deal of construction in the area threaten the structure if left undesignated. We ask the Commission to designate 57 Sullivan Street as an Individual Landmark, thus preserving this house in perpetuity.

Item I-E

JAMES MCCREERY & COMPANY, 801-807 Broadway, Manhattan

LP – 0206

Landmark Manhattan Block: 563 Lot: 37

This 1868 cast-iron building on the corner of East 11th Street and Broadway is a relic of the original Ladies’ Mile, which stretched from East 8th Street north to East 24th Street along Broadway. This corridor featured large shops, such as the James McCreery & Company store, the original tenant of this massive structure. After a number of tenants, the building fell to its nadir in 1971 when a fire destroyed its mansard roof and much of its interior.

However, it is always darkest before the dawn. Shortly after the fire, in 1973, the building received new life and was one of the earliest upscale cast-iron residential conversions. The building’s developer planned to build a new skyscraper on the lot, but after community input, it was decided that the building would be saved. Revolutionary at the time, the BSA granted a variance that eliminated the need for a 30-foot rear yard for a residential building based on the 16-foot window openings, which were deemed acceptable for adequate air and light. The BSA also allowed the construction of an upper story, designed by architect Stephen B. Jacobs, to add additional rentable square footage. The building as a residence continues to be a success, as tenants enjoy their spaces from behind a magnificent cast-iron Corinthian colonnade.

801 Broadway was beloved enough in the early 1970s to be saved, and its conversion was instrumental in the way real estate evolved to embrace adaptive reuse in New York City. The addition, while not flattering, is of its time and does not detract from the building. We urge the LPC to designate this unofficial landmark into a legitimate one, so that a bit of old New York—even 1970s New York—remains in the Village.

Item 1-F

138 SECOND AVENUE, Manhattan

LP – 2357

Landmark Site: Manhattan Block 450, Lot 5

138 Second Avenue is a Federal-style rowhouse, built in 1832 by Thomas E. Davis, a prolific developer of grand, late-Federal style houses in the East Village, few of which survive today. Of those that do survive, Nos. 4 and 20 St. Mark’s Place have both been designated Individual Landmarks. 138 Second Avenue bears much in common with these houses, including the handsome and elaborate Gibbs door surround, the Flemish bond brickwork, and the impressive scale of the house.

The house was, according to a 1916 New York Times article, the home of the League of Foreign-Born Citizens, a “non-racial, non-sectarian organization, founded in 1913, for the purpose of interesting the immigrant in civic affairs and inspiring those who had not been naturalized to take steps towards making themselves American citizens…owing to the gift of $1,500 from Mrs. Vincent Astor…the League…is enabled to move into a new clubhouse [at 138 Second Avenue]…”

The building was proposed for designation by the LPC in 2009, and has since been beautifully restored. 138 Second Avenue is a rare, intact link to the days when this stretch of Second Avenue was one of the premiere residential addresses in New York. Its alteration with added stories when converted to multi-family use, and small commercial addition in front, reflects the Lower East Side’s transformation by immigrants, and the emergence of Second Avenue in the early 20th century as the “Yiddish Rialto,” one of New York’s most vibrant entertainment centers. At the time of the hearing in 2009, the proposed designation of 138 Second Avenue enjoyed strong support from both local and city-wide preservation organizations.

Such well-preserved Federal buildings are rare and precious. We urge the Commission to prioritize it for designation.

Item 1-G

2 OLIVER STREET, Manhattan

LP – 0560

Landmark Site: Manhattan Block 279, Lot 68

2 Oliver Street is a Federal Revival style single-family dwelling, built on a side-hall-plan in 1821, with a third story added around 1850. Its simple design and features reflect characteristics representative of many such Federal-era residences, and the third story addition is done in a manner quite typical for such early relics of New York’s first wave of urban development. It is a contributing property in the Two Bridges National Register Historic District.

The building is additionally significant for having served as the home of James O’Donnell, one of the first trained architects in America. O’Donnell worked on the nearby Fulton Street Market while living at 2 Oliver Street, and later moved to Montreal to design the Basilica of Notre Dame. 2 Oliver Street had a public hearing in 1966, but was never designated. The effort to designate the structure was revived by local advocates and preservation organizations in 2002, and enjoyed strong support from local elected officials. We urge the Commission to designate this rare and well-preserved Federal dwelling.

Item I-H

INTERBOROUGH RAPID TRANSIT POWERHOUSE, 850 12TH Avenue, Manhattan

LP – 2374

Landmark Manhattan Block: 1106 Lot: 1

Stanford White was able to design in 1904 what today seems like a minor miracle – a utilitarian structure that was highly elegant and ornate. It was all in a day’s work, though, for White and other City Beautiful proponents who believed that public improvements should be built to create a city that was both functional and beautiful. We have them to thank for many of our city’s finest landmarks, including libraries, schools, bathhouses and parks.

With one glance at the Powerhouse, it is easy to see it is already a landmark, and deserves official recognition to ensure its survival. This monumental structure is a remarkable example of Beaux-Arts design applied to a utilitarian building; its architectural grandeur meant to convince the public to embrace the subway, a major new mode of transportation back in 1904. Designed as a showpiece, it now stands as a monument to progress and rapid transit. In addition to its architectural significance, the building holds an important place in industrial history. When it opened 111 years ago, it was the largest powerhouse in the world and provided the energy needed to run the first subway line along Manhattan’s west side, which in turn created and enabled the modern city of New York.

Despite the unfortunate loss of its original smokestacks, the IRT Powerhouse remains a commanding presence. With major development projects looming on all sides, this structure is a dynamic anchor for an ever-changing west side. With wide-spread support, the building has been proposed and heard for designation three times before. While this support network has not waivered, the building’s uncertain future grows more and more threatening. HDC urges you to designate this masterpiece before it is too late.

Item I-I

MISSION OF THE IMMACULATE VIRGIN, 448 West 56th Street, Manhattan

LP – 2360

Landmark Manhattan Block: 1065 Lot: 1

Tucked away on West 56th Street is a three-story, brick and limestone structure completed in 1903 as the midtown branch of the Mission of the Immaculate Virgin. The Catholic charity provided shelter, food, clothing and education for underprivileged boys. Designed by the firm of Schickel & Ditmars, which specialized in ecclesiastical and institutional architecture, this Beaux-Arts style building features many intact original features, including a rusticated limestone base, elaborate window surrounds and a dentilled, pressed metal cornice. The handsome building is an intimate anomaly within a streetscape of tenement buildings and warehouses, with the Hearst Tower and midtown skyscrapers within close proximity and view.

Item II-A

BERGDORF GOODMAN, 754 Fifth Avenue, Manhattan

LP – 0735

Landmark Manhattan Block: 1273 Lot: 33

Bergdorf Goodman, completed in 1927 after designs by Buchman & Kahn (exterior) and Shreve & Lamb (interior) and Robert W. Allen (entrance hall) is one of the rare buildings about which one can truly say that it is unique. It is significant for its inventive, refined design, which creates the illusion of a historical old world streetscape by breaking down the building mass into several smaller units. These narrow building elements – roughly 25 feet wide – and the distinctive slate roof, a defining feature of the building, recall the scale, texture and skyline of older townscapes.

The design is organized in a series of bays with a tight rhythm of windows in a vertical proportion. The detailing is extremely refined, using delicate, shallow changes of planes to create lines, shadows and decorative figures in the white South Dover marble material of the façade. The strong classical organization and urban character of the building has been able to assimilate an alteration by Allan Greenberg, which, no doubt, the Commission would approve today if the building had been landmarked.

Not only is the building significant for the high quality of its design by an important modern architect, it is also significant for its intended role in the urban context, a role that it still fulfills today. An article in the magazine Through the Ages (March 1931) noted:

“The exterior in the Louis XVI style, is of white marble, including the cornices, thus bringing it into harmony with the others facing the Plaza – – and with the Squibb building at the southeast corner of Fifth Avenue and Fifty-eighth Street. This is one of the cases where consideration was given to the neighboring architecture, a procedure that is unfortunately too infrequently carried out.”

It is a great fortune for New York that this urban environment can still be experienced today: the Squibb building at 745 Fifth Avenue, also designed by Ely Jacques Kahn, continues to be a beautiful presence in this urban landscape, as do the Pierre Hotel, the Sherry Netherland hotel and the Plaza Hotel, three New York City Landmarks.

We urge the Commission to recognize the architectural and urban significance of the Bergdorf Goodman building by designating it a New York City Landmark.

Item II-B

EMPIRE THEATER (Interior & Exterior), 236-242 West 42nd Street, Manhattan

LP – 1331

Landmark Manhattan Block: 1013 Lot: 50

Item II-D

LIBERTY THEATER (Interior & Exterior), 234 West 42nd Street, Manhattan

LP – 1344

Landmark Manhattan Block: 1013 Lot: 12

Item II-E

LYRIC THEATER (Exterior & Interior), 213 West 42nd Street, Manhattan

LP – 1353

Landmark Manhattan Block: 1014 Lot: 39

Item II-F

NEW APOLLO THEATER (Interior), 215-223 West 42nd Street, Manhattan

LP – 1363

Landmark Manhattan Block: 1014 Lot: 20

Item II-H

SELWYN THEATER (Exterior & Interior), 229-231 West 42nd Street, Manhattan

LP – 1377

Landmark Manhattan Block: 1014 Lot: 17

Item II-J

TIMES SQUARE THEATER (Exterior & Interior), 215-223 West 42nd Street, Manhattan

LP – 1382

Landmark Manhattan Block: 1014 Lot: 20

Item II-L

VICTORY THEATER (Exterior & Interior), 207 West 42nd Street, Manhattan

LP – 1384

Landmark Manhattan Block: 1014 Lot: 25

These seven theaters along West 42nd Street, all calendared in 1982, were overlooked for a reason. Times Square of the “Midnight Cowboy” era was run-down, under-populated, and considered unsafe. A recession in the mid-1970s, “white flight”, and a declining tax base left New York City desperate. Many historic theaters had already been chopped up into multiplex cinemas.

In 1973, John Portman, Jr. proposed to build a 50-story Marriott Marquis Hotel on Broadway between 45th and 46th Streets. This project would require the demolition of 2 former theaters (then cinemas), and three functioning Broadway houses – the Morosco, Bijoux, and Mary Martin. This news excited the business community, but galvanized actors & preservationists to protect what was left of the theater district.

Letters & op-eds were written, rallies were held, but by the early 1980s real estate interests had triumphed, and in 1982 steam shovels cleared the site. It is little wonder that at around this time most of the remaining theaters had been submitted to the LPC for designation as Individual Landmarks. In 1979 the New Amsterdam was designated, in 1982 the Little Theater (renamed for Helen Hayes) was designated, and in 1985 the interior of the Ambassador was designated. In 1987, twenty five additional theaters were designated by the LPC.

The seven remaining theaters were skipped over because by the mid-1980s the City and State of New York had created an Economic Development Corporation as a vehicle to “clean up” both sides of 42nd Street (between Broadway and Eighth Avenue). All of the houses below were acquired by eminent domain for the New 42nd Street, established in 1990. They developed an overall urban renewal plan, and turned over the theaters to individual developers for restoration or new construction. Because this entity was exempted from City regulations, the LPC was no longer able to consider the properties on their merits for designation.

What has happened to these properties since, while admirable in many ways, represents a broad range of approaches to renovation. The New Victory was restored, the Apollo interior incorporated into the Lyric, the Empire relocated and expanded, the Selwyn and Liberty refaced. The Times Square still awaits restoration. They are all worthy of Landmark designation, despite the de-construction of some elements.

In the early 1980s, West 42nd Street between 7th and 8th Avenues was a neglected stretch of urban decay. New York residents and visitors avoided the area, and a growing public concern compelled New York State and City to join forces to eradicate the blight. The New 42nd Street was established by these public entities in late 1990 to assume long-term responsibility for the block’s seven historic theaters—The Victory, Times Square, Selwyn, Lyric, Liberty, Empire and Apollo. With this 99-year lease came the obligation to not only restore these theaters, but to create a new entertainment district for the 21st Century.

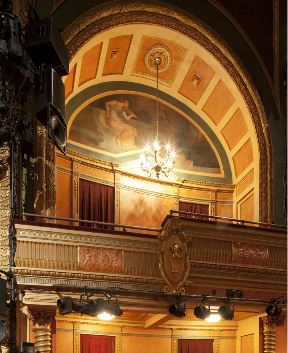

In 1991, aware of the risks involved, The New 42nd Street bravely chose the least desirable property under its aegis—the double-balconied 499-seat Victory Theater—to restore and reinvent first. The staff and board conceived the revolutionary idea of inviting kids and families to 42nd Street, and—after eighteen months of design and construction—proudly reopened the doors to The New Victory Theater on December 11, 1995, dedicating the oldest operating theater in New York City to its youngest theatergoers.

Gone is the blighted, hostile 42nd Street landscape of 1990. Today, 42nd Street is thriving and spirited with a vibrant mix of nonprofit, commercial and cultural institutions. Throughout the year, at any time during the day or night, Times Square plays host to New Yorkers and visitors from around the world as New York’s premier destination for popular art and entertainment, presenting the nuances of its glorious historic, cultural and architectural past.

Item II-C

HOTEL RENAISSANCE/COLUMBIA CLUB, 4 West 43rd Street, Manhattan

LP – 2070

Landmark Manhattan Block: 1258 Lot: 42

Originally the Renaissance Hotel, the building was designed by architect Clarence Luce and was constructed in 1890-91 as an apartment hotel for young men. By the turn of the 20th century, this neighborhood had changed dramatically and became fashionable, with theatres, hotels and clubs abounding. The Columbia Club moved into this location in 1915, departing the former club district of Gramercy. Many other clubs followed suit and eventually this area, centered around West 43rd and 44th Streets between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, emerged as the “Clubhouse District”.

This palazzo-style building is remarkably intact, save for its windows, including original storefronts, which is astounding in such proximity to the dynamic retail of Fifth Avenue. It is thought to be the only extant example of a Renaissance Revival hotel in New York City. This early style is reflective of the 1890s development in this area, making it significant as most hotels in this neighborhood date to the early 1900s and were rendered in a Beaux-Arts design, making the aptly-named Hotel Renaissance a rare survivor.

Item II-G

OSBORNE APARTMENT INTERIOR, 205 West 57th Street, Manhattan

LP – 1166

Landmark Manhattan Block: 1029 Lot: 27

The Osborne’s interior is a remarkable gem within the bustle of ever-changing 57th Street in Manhattan. Completed in 1885, the building’s intact interior is evocative of the panache and glimmer that defined the Gilded Age. The space glows with warmth and opulence, featuring Italian marble wainscoting and carved marble recesses with benches. The floors are mosaic tiles and marble, and the arched ceiling is treated in vibrant hues of red, blue and gold.

This interior masterpiece was designed by Jacob A. Holzer, whose peers in artistry included John LaFarge and Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Often overshadowed by these artists, the equally talented Holzer completed most of his works in Chicago. The Osborne lobby is New York’s only known work by Holzer, and it is truly a gift. Five years after this work at the Osborne, in 1895, the immensely talented Holzer became the chief designer at Tiffany, and is credited with creating an electrified lantern prototype which served as the predecessor for the Tiffany Lamp.

Item II-I

SIRE BUILDING, 211 West 58th Street, Manhattan

LP – 2359

Landmark Manhattan Block: 1030 Lot: 25

This early flats building was commissioned by Benjamin Sire, a wealthy real estate magnate whom history has all but forgotten, save for his name emblazoned atop this building. The architect, William Graul, was a prolific architect of flats and tenement buildings. Much of his work remains scattered throughout Manhattan, and his original office still stands at 215 Bowery, in the Germania Bank.

Tucked between Broadway and Seventh Avenue, the Sire Building has remained virtually unscathed on West 58th Street since 1885, and this building is emblematic of the first wave of development in the neighborhood. What’s more, this building has remained despite the drastic high-rise construction that characterizes midtown. Its lively façade is rendered in High Victorian with Neo-Grec details. The commercial ground floor has been replaced, but the building retains its original carved wooden doors on its western bay. This structure is a relic, and deserves to be preserved as one example of early residential development, when 58th Street was of a more human scale.

Item II-K

UNION SQUARE PARK, Manhattan

LP – 965

Landmark Manhattan Block: 845 Lot: 2

Closed as a potter’s field in 1807, Union Place was laid out in 1811 at the union of Bloomingdale Road (Broadway) and the Bowery (4th Avenue), and stretched from 10th to 17th Streets. This confluence of streets was reduced from 14th to 17th streets in 1832, and the park was named Union Square at that time and consisted of a fenced-in oval in the middle of the square. In 1872, the park was redesigned by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux to suit large congregations of people, so the fence around the park was removed and a fountain was introduced to the center of the oval. The park was altered again in 1936 when the BMT subway was constructed, raising the park above grade on a four foot platform and park pathways were straightened, and the pavilion was constructed. Several renovations by the Parks Department in 1985 and 2005 have further altered the WPA era Union Square.

With two centuries of changes to the park, it is difficult to determine original historic fabric; moreover, what fabric from which period of time. Monuments within the park, the oldest being of George Washington erected in 1856 remain in situ, yet their surroundings have been completely reconfigured. One monument, the World War I memorial dedicated on Armistice Day 1934, has been removed altogether, and now lives on 23rd Street outside the Veterans Hospital. Union Square was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1977, its period of significance acknowledging the first Labor Day on September 5, 1882, when workers assembled en masse on the open north plaza. While the entities responsible for the stewardship of the park have been studious about interesting improvements, they have not had a good history of respecting its heritage and unfortunately, the park has been a magnet for accretions. The north plaza no longer is an uninterrupted expanse, undermining its claim to fame. Because of the lack of historic integrity, HDC does not support designation of Union Square as a New York City Scenic Landmark.